Q: “I have an IFU that requires a lint-free cloth, but I am having a hard time finding a cloth that is sold as lint-free. Why can’t I find one?”

A:

I receive this question via email a few times every year, and I never feel like I have enough space to fully explain the situation in an email response. So, let’s see if we can untangle our way through a potentially hairy situation and try to weave a narrative, tying in some scientific studies, and rolling in some clarification on lint terminology. (Author sincerely apologizes for these terrible attempts at lint humor.)

First, let’s talk about lint itself.

Merriam-Webster1 defines it as:

- “a soft fleecy material made from linen usually by scraping.”

- “fuzz consisting especially of fine ravelings and short fibers of yarn and fabric.”

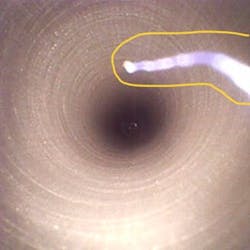

In the healthcare space and, specifically, in sterile processing, our lint is typically made of fine fibers that separate from items like wraps, towels, and other textiles. Like their partner in grime (dust), lint is usually very lightweight, and it can be carried on air currents and deposited anywhere. It can also attach itself to instruments and devices and is notorious for getting snagged on the jagged jaws of instruments and finding its way inside our many lumened devices. (Fig. 1).

There are various types of linen or textile materials. We have woven materials (in which the fibers are sewn or interwoven together) and non-woven materials (where fibers are fused or bonded together using a chemical, mechanical, or solvent process). Whether woven or non-woven, they both use very fine fibers, which can separate from the whole to create what we call “lint.”

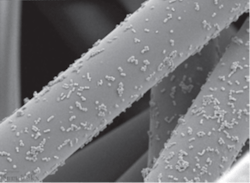

Is lint dangerous? It can be! From ANSI/AAMI ST79:20173 (Section 3.3.6.2), “Lint and airborne particles can carry microorganisms.”3 Bacteria, spores, and other pathogens love linen fibers because a) they can retain moisture and b) there are plenty of fibrous dark areas inside that are ideal breeding grounds of them to grow and develop.

I would like to direct you to the research of Dr. Wava Truscott, Ph. D.-MBA. A quick Google search of “Wava Truscott lint,” pulls up some incredible research and findings on how damaging lint can be in various forms.

In an article by Dr. Truscott in Biomedical Instrumentation and Technology called Lint Fiber–Associated Medical Complications Following Invasive Procedures4, she writes, “The most prevalent complications associated with lint contamination of surgical wounds include thrombogenesis (blood clot formation), infections (increased frequency, severity, biofilm formation), amplified inflammation, poor quality wound healing, granulomas, and adhesions.”4

But it’s not just the threat of pathogen exposure from lint (Fig. 2) that we need to worry about. ANSI/AAMI ST79:2017 (Section 8.4) states, “Non-linting materials are recommended because lint can be introduced into a patient’s wound and cause a foreign-body reaction.”3

Let’s examine a real-world scenario. You’ve done an excellent job following the Manufacturer’s (Mfr.’s) instructions for use (IFU) for your instrument or device through the decontamination process and have a clean device as a result. During the assembly process, there is a towel placed on the workstation that you are assembling on, and some microscopic fibers from that towel make their way onto your clean device and into your tray. You may be tempted to believe sterilization will kill any harmful microorganisms, so there’s no harm in some lint in your tray; right? Wrong! Even if the lint has been sterilized inside a sterile barrier, if it’s allowed to escape via instrument or airflow into a patient’s incision, it can have devastating impact.

In our above example, if our sterilized lint enters a patient’s bloodstream, the body will treat it as a foreign body, and it triggers the vascular defense system. Clotting begins to “wall off” the foreign invader and forms a sort of “net” inside the blood vessel to hold it and keep it from traveling farther into the bloodstream. This clotting continues to grow and trap more blood cells or foreign material, which then forces blood flow and pressure to increase from behind to get around it. If the force is significant enough, it can tear the clot from the vessel and into the bloodstream. This clot becomes what is called a foreign body embolus. Blockages of blood vessels, or embolisms, can occur, and organs behind the embolism can become oxygen deprived, damaged, and even necrotic (infarction).4

There’s also a risk of what is called immune distraction (where the foreign body/lint enters the patient), and while the immune system is distracted fighting off the larger foreign body (that the lint presents), other damaging pathogens are allowed to survive, find protected pockets inside the body, and thrive.

So, Adam, what does all that have to do with the terminology of “lint-free” or “non-linting”?

Well, for one, the term “lint-free” doesn’t really apply to any woven or non-woven linen or textile. At least not after being removed from the packaging or having been handled.

Have you ever had a bathroom or kitchen towel or maybe even a favorite shirt that over time started tearing or “pilling”? The more handling of a linen (the more friction applied to the fibers), the more likely it will result in lint. All fibers, given enough wear and tear, or enough usage, will start to separate from the bunch. This phenomenon is what we call lint. Rub two sides of a lint-free cloth together and watch as the "lint-free" cloth magically produces lint!

This phenomenon is why the language in ANSI/AAMI ST79:2017 (Section 7.4.1) states, “Cloths used in decontamination should be clean and non-linting and should be changed frequently.”3 Non-linting is simply more accurate terminology to describe the cloth. It can’t really be lint-free because it’s made of fibers that can lint; however, when it arrives, it’s not actively linting because it’s arriving in a non-linting form. Thus, the term “non-linting” was born.

If you have an IFU asking for a “lint-free” towel (Fig. 3), it’s likely it was written prior to 2017 when that terminology was more prevalent and included in older editions of the standards.

ISO® (ISO 9073-10)7 (Fig. 4) and European standards have done extensive testing on textiles to determine particle counts of lint and other particles generated from a dry state. They created a “coefficient of linting,” which is the “log of the particle count applied to all or to a part of the measurement channels.”7 In plain English, that means a count of how many foreign body particles are shed from non-woven materials and a baseline for what should be considered non-linting or “low-linting” (which is the preferred terminology in Europe).

Reusable towels are the biggest culprits of lint creation in the sterile processing environment and should be avoided, if possible. Some suggested solutions to our ever-accumulating lint problem:

- Non-linting liner alternatives can be used inside trays and on your workstations.

- Shelf liners can be used on your autoclave racks and carts to avoid using linty towels as wicking materials.

- Personnel in the sterile processing department should be wiping their workstations at the beginning and end of their shifts to prevent the accumulation of dust and lint.

- Routine and recurrent cleaning of the environment for places where dust and lint collect.

So, there you have it.

There really isn’t such a thing as a lint-free cloth, but if you encounter this terminology, you’re really looking for a cloth that is not actively linting, or, in other words, non-linting.

Does your head hurt as much as mine does? I think I need to put a cold, non-linting compress on it.

References (APA Style 7th Edition):

-

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.) Lint. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved March 10, 2025, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/lint

-

Rojo, C. (n.d.). Inside a lumened device [Photograph]. Healthmark, A Getinge company.

-

AAMI (2017). ANSI/AAMI ST79: 2017 Comprehensive guide to steam sterilization and sterility assurance in health care facilities. Arlington, VA: Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation.

-

Truscott, W. (2023). Lint Fiber-Associated Medical Complications Following Invasive Procedures. Biomedical instrumentation & technology, 57(s1), 5–10. https://doi.org/10.2345/0899-8205-57.s1.5

-

Truscott, W. (2014). The Clinical Issue: Foreign Debris In Post-Surgical Complications [Photograph: Lint fiber with bacteria on p 2], Knowledge Network Kimberly-Clark Healthcare Education, Issue 8, 1–8.

-

V. Mueller Division. (2012). V. Mueller® Products and Services General Surgical Instrument Cleaning and Sterilization Guide. CareFusion Corporation.

-

ISO®. (2003, May; Confirmed 2019). ISO 9073-10:2003 Textiles — Test methods for nonwovens — Part 10: Lint and other particles generation in the dry state. (1st ed.). International Organization for Standardization.

Adam Okada | Clinical Education Specialist, Healthmark, a Getinge company

Adam Okada has 18+ years of experience in Sterile Processing and is passionate about helping improve the quality of patient care by giving SPD professionals and their partners greater access to education and information. He has worked in just about every position in the Sterile Processing Department, including Case Cart Builder, SPD Tech I, II, and III, Lead Tech, Tracking System Analyst, Supervisor of both SPD and HLD, Manager, and now as an Educator. Adam is the owner of Sterile Education, the world’s first mobile application dedicated to sterile processing education, and a former Clinical Manager at Beyond Clean. He has published articles for HSPA’s Process magazine, is a co-chair on AAMI WG45 as well as co-project manager for the KiiP “Last 100 Yards” group, and is the former President for the Central California Chapter of HSPA. Adam is currently a Clinical Education Specialist at Healthmark, A Getinge company, where he works on Healthmark webinars, hybrid events, and educational videos, as well as the "Ask the Educator" Podcast with Kevin Anderson.