The problem is all inside your head, she said to me. The answer is easy if you take it logically”…

So begins one of the best-known songs in the long and iconic career of Paul Simon. “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” is an instruction manual for how to get out of a bad relationship. One of the 50 ways Simon advocates is to “Make a new plan, Stan,” which is something that many organizations in healthcare found they needed to consider after the many disruptions and problems that surfaced during the last two years.

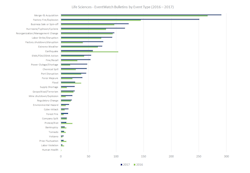

Click to view full size graphic

Companies that rely extensively on people’s knowledge of suppliers and supply chains are slower to respond, find it difficult to adapt and take evasive action when supplier dynamics shift. As you may have read in the previous two parts of this three-part series, supply chains get disrupted every day due to many different reasons. In 2017, there were almost 300 supplier factory fires in the Life Sciences industry. But supply chains can get disrupted from so many other events. On average, every two hours, something happens somewhere in the world that has implications for supply chain practitioners today.

So it becomes imperative to “Make a new plan, Stan…”

Making a new plan is not something that comes readily to healthcare, especially in its supply chain. When disasters strike, the industry’s history has been to respond, react and return to normal after the crisis passes. But the upheaval caused by the disasters of the last two years, including the devastating impact on manufacturing facilities that produced key supplies, has given healthcare professionals pause.

Maybe it is time to “Make a new plan, Stan.”

Here are some things that Supply Chain leaders learned last year that were heretofore either completely unknown or worse yet, not even considered:

-

Organizations knew on whose trucks supplies came to the dock, but they didn’t know:

-

What company manufactured them

-

Where they were manufactured

-

Where the components that made up the products were manufactured

-

-

Organizations did not have a ready list of alternative suppliers for key items

-

Manufacturers often used single-source, single-manufacturing site sub-contractors for key components of their products. Manufacturing redundancies were often absent, putting entire product lines at the mercy of Nature.

-

Worse yet, most organizations had neither the capacity for nor the understanding of why and how predictive analytics could be brought to bear before disaster struck.

On March 14, 2018, I attended the 2018 Symposium on Health Sector Supply Chain, presented by the W.P. Carey School of Business at Arizona State University. The title of the Symposium was: “Puerto Rico Matters — Lessons for Managing Risk in the Health Sector Supply Chain.” Its introduction stated:

The Impact of Hurricane Maria on U.S. Health Care Delivery

The 2018 Symposium on Health Sector Supply Chain focuses on vulnerability in the health care supply chain. The Symposium idea has its origin in the host of problems facing the over 45 medical device and pharmaceutical companies impacted by Hurricane Maria in 2017. While many companies were “up and running” quickly, others experienced problems due to damage to their plants as well as continued problems related to access to power and employee access to work.

Supplies, purchasers and distributors are challenged to design risk mitigation strategies to assure continuity of care. Policy makers are challenged to direct resources at the times of crisis – but of even greater importance, to craft policies that anticipate risk and mitigate risk.

Puerto Rico Matters:

-

Shortly after the hurricane, the American Red Cross was faced with a shortage of bags for collecting blood. Hospitals across the U.S. have recorded periods of limited operations due to hurricane related shortages.

-

“The bag shortage is the most significant to be directly linked to the effects of the hurricane, but others are likely to follow.” New York Times (October 24, 2017)

-

“Supply shortage tests hospitals”. The Wall Street Journal, January 8, 2018

-

Join with us to:

-

Explore perspectives from suppliers, providers, distributors and policymakers

-

Consider consequences to patients

-

Understand the role of supply chain strategy to mitigate risk (Source: W.P. Carey School promotional leaflet).

Speakers at the symposium ranged from providers and key IDN executives to GPO representatives to professionals from both the healthcare and non-healthcare segments. The message was clear: Disruption is omnipresent, and disruption can be mitigated by focused planning.

The final two questions I posed to the providers and suppliers I interviewed were:

-

How did the event(s) change the way you do business on a go-forward basis?

-

What were your biggest takeaways from the experience?

Both suppliers and providers saw the need for better inventory planning.

David Myers, Executive Vice President and Chief Customer Officer at Concordance, cited the need for focusing on key items and increasing on-hand supply levels, and Nicholas Johnson, Materials Manager at the University of Vermont Medical Center said, “The supply interruptions caused by both Maria and the extended flu season provided the motivation for our supply chain to review what inventory policies to use for the different product categories. With the need to maintain continuity of supply while keeping an eye on cost containment, our supply chain reviewed how many days of supply was prudent based on the criticality of an item, the cost, the ease with which to introduce a substitute, etc.”

As for takeaways, once again, Johnson offered useful advice for the path forward, saying, “A supply chain’s best laid out plans can still be negatively impacted by unforeseen upstream events. Having visibility to what needs attention most in these situations is imperative and requires good data and being able to present that data in a meaningful and actionable way. Having a collaborative multifunctional team to assist with decisions is also needed. Having the knowledge base of a team with the data allows for creative decision making so ongoing communication is needed as well. With data, people and ongoing communication, the best decisions were made to allow our hospital and network to weather what has been a very disruptive six months.”

Compared to most, Johnson may just be the Nostradamus of the healthcare supply chain as it relates to risk mitigation and business continuity planning. While many talked about incorporating lessons learned into future activity, Johnson hinted at the solution: Develop a formal Risk Mitigation/Business Continuity Plan and arm it with the components needed to ensure success:

-

People

-

Process

-

Technology

-

Data

Prior to my attendance at the meeting in Tempe, I had attended an internal meeting at J.A. Sedlak in which Dennis Heppner, one of the company’s senior logistics consultants, had described an engagement with a retail customer that involved the development of “what if” scenarios regarding work disruptions at the organization’s manufacturing sites. I was intrigued by two aspects of the presentation: 1. technology existed to create algorithms that could predict the impact of such things and 2. an organization would be so forward-thinking as to provide resources (both fiscal and human) to proactively deal with the issue.

I asked Heppner to explain what he and his team did for the customer.

“We created a model that quantifies the impact of various disruptions in the network (from catastrophic loss to less severe partial disruptions),” he responded. “Additionally, Decision Trees and communications plans (internal and external) provide actions to be performed…. This includes direct labor associates, appropriate functions such as Supply Chain, IT, Real Estate and HR, as well as suppliers of inventory and services (transportation, temp labor and real estate brokers). While every contingency is not feasible to model, the most likely and impactful scenarios provide the client with a plan to react.”

The work done by Sedlak for the retail customer incorporated two of the four elements of a successful plan: Process and Technology. The retail company’s commitment to doing something provided the third: People. What about the fourth: Data?

One of the speakers at the symposium in Tempe was Bindiya Vakil, Co-founder and CEO of Resilinc, a company that maps the supply chain down to part and site level, and aggregates and provides this data to help organizations predict their critical failure points so they can develop proactive management strategies to mitigate risk and ensure business continuity.

Describing the problems faced by organizations, Vakil said, “Supply chains have become tiered, and suppliers are operating all over the world. One supplier can operate in 10 to 20 countries, and raw materials and components could travel two to three countries before making their way to our factories.

“Most companies know their direct suppliers,” she continued. “They often know where their direct suppliers are located, but may not always know the specific global sites that build each raw material. This type of information is not systematically available, but rather is known by the people who manage these suppliers.

“Even more problematic is that suppliers may use common sources and so dual-sourcing at the tier 1 level may still leave the company exposed to sub-tier risk.

“This type of information is not typically available, or if it is available, it resides in people’s heads/laptops and remains siloed within the organization. In a highly complex supply chain environment where hundreds of suppliers make thousands of raw materials in 40 to 50 countries around the world, having information in siloes makes it difficult to predict problems quickly and respond/mitigate proactively. As a result, most companies hold high levels of inventory, and when that is not available, end up paying massive premiums to acquire raw materials during a disruption/allocation situation. If they are unable to act quickly to secure sufficient supplies, they may end up going on allocation, or their factories may go lines down due to lack of materials. This leaves cash tied up in WIP [works-in-progress] inventory or finished goods that cannot be shipped due to small inexpensive parts being disrupted. Worst case, customers may buy other materials, or in the case of healthcare sector, it might be a life-threatening situation if the patient is unable to get treatment or drugs.”

Resilinc becomes a source of the fourth element of a successful plan: Data.

What would a successful plan look like? Here are my thoughts:

-

People: Healthcare organizations are often reticent to commit resources (i.e., FTEs) to a problem. They simply pile additional tasks onto an already overburdened staff. Business Continuity Planning requires specific skill sets and a full time concentration of activity. Without a dedicated resource leading the initiative, it is destined to fail.

-

Process: Given the presence of assigned resource(s), a formal Business Continuity/Risk Mitigation Plan should be developed, approved and put into action. This could be done alone, but would most likely require outside assistance to get started.

-

Technology: Scenario planning and “What-If” gaming, such as that done by Dennis Heppner’s team at Sedlak, can help ready an organization for anything that might occur.

-

Data: Participation in an ongoing subscription service such as Resilinc would keep organizations abreast of and thoughtful of the fluid and dynamic changes everyone faces every day.

That said, organizations need to be mindful of the need to plan and also of the need to bring People, Process, Technology and Data into the mix. It’s not as simple as Paul Simon advocated. You can’t:

Just slip out the back, Jack,

(you’ve got to) make a new plan, Stan

Don’t need to be coy, Roy

just listen to me

Hop on the bus, Gus

you do need to discuss much

“Planning’s the key, Lee

It will get yourself free.”