Dartmouth-Hitchcock team pulls Supply Chain through pillars of progress

Since 2017, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health’s Supply Chain philosophy seems to have reflected the art and science of creating structure with LEGO blocks or Minecraft: If you build it success will come.

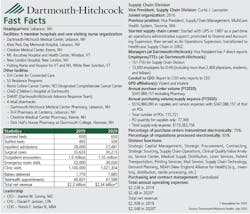

To Curtis Lancaster and his Supply Chain division team at the Lebanon, NH-based integrated delivery network that pokes into neighboring Vermont, Supply Chain as a category, descriptor, function and even title may not accurately befit what they do anymore.

In fact, they’ve punched through the traditional stereotype of simply moving boxes of stuff by pursuing and embracing deeper and more meaningful roles such as strategic planner, sourcing enabler, margin-enhancement deliverer, demand-planning innovator, communication facilitator and administrative ace-in-the-hold for the C-suite. They have remodeled and reconstructed their infrastructure around a quartet of performance improvement pillars of operation: people, technology, trade and innovation.

Four years ago, an academic medical center and teaching hospital anchored a loose federation of hospitals and clinics that lacked a cohesive supply chain engaged in many decentralized activities, according to Lancaster. Since then, they have centralized and vertically integrated supply chain activities that increased value system-wide and extended savings regionally.

“It’s been our mission to look and act like a system,” Lancaster admitted. “Each of our sites had their own independent supply chain, and we have worked hard to pull together as a system supply chain supporting each local business unit/system member.” Dartmouth-Hitchcock also is one of the founding members of a regional purchasing collaborative called Northeast Purchasing Coalition (NPC) and leads supply chain initiatives and sourcing with local vendors for an alliance of more than 25 hospitals in New Hampshire and Vermont called New England Alliance for Health (NEAH). Dartmouth-Hitchcock accesses many supply and service contracts and initiatives through Vizient.

The Dartmouth-Hitchcock Supply Chain team doesn’t take whatever lessons learned and success achieved from their demand-planning process and COVID-19 response for granted. They continue to scan the horizon to justify their mantra and motto to “think different” and “support the hands that heal.”

For these reasons and their relentless pursuit of what’s next, Healthcare Purchasing News selected the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Supply Chain division as its 2020 Supply Chain Department of the Year.

People matter

Five years back the Supply Chain department at Dartmouth-Hitchcock functioned more like an extended-stay truck stop, a place where professionals entered to freshen and refuel their career goals before venturing to another area on the next leg of their occupational journey. The recurring tactic wreaked havoc on consistency as hiring and retraining to attain the desired effectiveness and efficiency occupied daily activities.

To morph into a nimble visionary team from a dysfunctional reactionary group required dedication, effort and time, starting with recognizing people as the impetus for and operator of redesign and technology use, and integrating people at every turn within the organization’s strategy.

Under Lancaster’s leadership, the Supply Chain division established people as a key pillar of the organization’s strategic plan in a roadmap for a dynamic group that gained leadership traction and visibility by turning challenges to opportunities and progressing through creativity. From this developmental progress, “we were at the table now,” he noted. When referring to Supply Chain’s pandemic sourcing, even their CEO remarked that the team “made a real impression – really phenomenal.”

As the team advanced, Lancaster points to key skills that were honed and tested, such as “scheduling as it creates the demand signal; perioperative where product knowledge and use is critical and where scheduling and logistics are critical success factors. And, let’s not forget system management where our recent experience leading through a crisis can be applied to leadership positions,” he said.

If anything, they strove to become a group that could perform daily with grit and skill to handle whatever faced them, even a once-in-a-century pandemic that disrupted everything, he reflected.

“[COVID-19] confirmed we had what it took. In many industries you drill and practice so that you will be prepared for a future event,” Lancaster told HPN. “Firefighters drill and prepare for when the fires come. Sports teams practice and prepare for the big game. As Mike Tyson explained in preparation for a boxing match, ‘Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.’ The pandemic punched us in the mouth … repeatedly. We learned that the mindfulness and resiliency we worked on, the communication and trust in each other kicked in like muscle memory. We trusted each other. We worked well together. The strategy directed us toward our goal, even in crisis: helping the hands that heal. Our ops director was in incident command and helped harmonize all our efforts.”

The onset of COVID-19 not only tested their resolve but amplified and showcased their 2019 game plan execution as they embraced their motto to “support the hands that heal.” Daily distractions came fast and furious, Lancaster added.

“Oftentimes people are viewed as cogs in a wheel when they are actually the grease that keeps things spinning,” he said. “This old mindset comes from the belief that supply chain is a transactional exercise and not a strategic pursuit. There is also a tendency to look forward and outward for the next enhancement and improvement and not keep the focus on developing and mentoring the teams.”

Traditionally, Supply Chain remained invisible and invited attention when something went wrong, according to Lancaster.

“Good things [can] go unseen and bad things make the loudest sound,” he said. “We rarely were recognized for the work we did, much like a lightbulb isn’t noticed until it is burned out and doesn’t do its job.”

Because Supply Chain had been operating in consistent performance improvement mode for several years, the emergence of the coronavirus and its escalation into a global pandemic that slammed national, regional, state and local supply chains, didn’t ignite a crisis for Dartmouth-Hitchcock’s Supply Chain team. They were fortified strategically and ready to act.

“Our response to COVID allowed us to shine,” he said. “We succeeded in meeting the needs. This was recognized throughout our system, including by our CEO. While a recent event, it echoed the path we were on to change the perception of the organization.

“Consistency and dependability matter to our customers,” Lancaster continued. “Things don’t change overnight; however, working with leadership and front line staff to best support them shows through action our team cares, that we listen. By doing this we gain buy-in for our initiatives or enhance understanding when errors are made.”

New roles, narrative

Strategically, Supply Chain created several new roles to fortify and manage through data analytics. The most dramatic change in roles, per Lancaster? The Demand Planner position, which came just in time for the coronavirus.

“We created it from scratch, applying what we learned from other industries balanced with what we needed to serve our trading partners,” he noted. [For more on Dartmouth-Hitchcock’s demand-planning process, read ”Demand-planning strategies predate pandemic, but produce perseverance” on page 16.

New positions also include a business manager to choreograph the data analytic work and reporting that is disseminated throughout the division; fully focused program managers Rosa Angulo and Claire Nerenz to specialize in selected areas, such as pandemic preparedness and regulatory compliance, and not double up for these tasks in addition to their regular jobs; dedicated legal counsel to facilitate the contracting process; an Item Master “master;” more analytically oriented specialists on Robin Boylston’s technology team, Lancaster listed.

Other new roles include professionals supporting the reprocessing of N95 respirator masks and the logistics of distributing the reprocessed respirators both internally and externally to system members; staff like Adam Stewart, who worked in a new forward-stocking location to satisfy the needs of critically-short supplied products while still rationing to ensure control over the supplies; staffing a new offsite warehouse that stocks product in bulk to be distributed to system members, the organization’s Service Center and NEAH members. “Lastly, we are performing scheduled rounding led by Operation Manager Hunter Fifield with the clinical team, who are directly supporting COVID-19-positive or -suspected patients to ensure proper PPE supplies,” he added.

Supply Chain created a marketing narrative that told their story. “This allowed for stakeholders to truly see what we did – at least on paper,” he said. “Our actions had to and did reflect the document. Readers seemed to gain an appreciation of the scope and challenge of our work. When you know the light is going to come on when you flip the switch, you don’t carry extra light bulbs around with you just in case. You know it is going to work, perform its function and provide illumination.”

Supply Chain also knew to initiate and develop partnerships with clinicians – doctors and nurses on the front lines and in the surgical areas. Preparation drove progress, according to Lancaster.

“We worked with [Dartmouth-Hitchcock] leadership to bring a part-time medical director, Dr. Shane Chapman, into the supply chain to help us better connect with physicians,” he indicated. “We focused on analytics to make sure we came to meetings with accurate financial data, clinical data and evidence-based research. We conducted one-on-one meetings with key service-line leaders to discuss opportunities, collaborate and build trust. We did this before any group meetings. Our staff joined many of the clinical and safety committees to make sure we were aware of emerging needs and articulate the help we could provide. Finally, we expanded Krista Merrithew’s value analysis team with additional registered nurses.”

Technology in rotation

When it comes to technology adoption and implementation, supply chain departments tend to fall into three distinct technology groups, indicated Richard Casano, Director, Supply Chain Operations.

The first reflects a group with not enough technology to be anything but reactive; the second possesses too many technologies that muddy the water, causing more confusion than clarity; and the third maintains the correct amount of technology to grow deep expertise and skill, he explained. They gravitated to No. 3, but acknowledged the ease to languish within No. 1, and become seduced and trapped within No. 2, making escape a challenge.

“I have colleagues who have every tool under the sun,” Lancaster said. “However, the tools don’t align to support an overall analytics strategy. Data and analytics are pillars of our strategic plan. Data should inform decision making; inform your course towards the beacon. And, you’ve got to fully use what you have. That means learning the tools, spending time with it, experimenting.

“Too many technologies can seemingly compete with each other,” Lancaster continued. “Teams can lose track of which technology is specialized in which arena or why they have it in place. If the technology is placed and never used or they compete and have conflicting data, the worth of the product is completely lost. Our team escaped this cycle by gaining support from senior leaders and clinical teams by listening to what their focus is, aligning our mission and vision statements with technology that will enable best practice, patient and employee satisfaction. Icing on the cake is always cost savings and increased value.”

Trade involves relationships

Dartmouth-Hitchcock’s Supply Chain division applies the term “trade” as shorthand for interactions among internal stakeholders, such as clinicians and patients, as well as with external partners, such as manufacturers and distributors. Some might classify this mindset as customer service, but Lancaster’s team plants it into their strategic plan as a foundation to “interact, process, benefit.”

For example, for the last several fiscal years, Supply Chain has exceeded its financial goals, contributed to enhanced margin and a healthy bottom line as well as integrated value over preference in product selections through clinical collaboration, data analytics and fiscal stewardship, Lancaster indicated. In fact, through data analytics the team identifies safety issues and leads efforts to reduce errors. One example is RASH, an acronym for “recalls, alerts, shortages/substitutions and hazards.” Still, Supply Chain remains “fully ingrained” in product and service decisions, safety, service and productivity directly and indirectly, he added.

Supply Chain’s Capital Equipment Manager Bob Simms actively serves on the Capital Committee for sourcing, analysis and contracting. Lancaster represents Supply Chain on the FTE Committee, which covers services contracts.

Focusing on value over preference can be difficult, according to Krista Merrihew.

“Getting stakeholders, specifically clinical stakeholders, to understand that we are striving to act as a system both financially and clinically is a challenge,” Merrihew admitted. “We want patients to have a consistent, customer-oriented experience when in our facility. Patients are more aware, perhaps more than we realize, and very cognizant of the products used on and in them. Consistency of products creates for a consistency of experience. With clinicians, we share financial and evidence-based product research to support sound decision-making.”

Supply Chain meets monthly with the certain clinical chairs to collaborate on product and vendor decisions.

As an example, by keeping close watch on contract terms and conditions, especially expiration dates, as well as collecting ample financial and clinical evidence on orthopedic and spinal products, Supply Chain was able to justify and rationalize discussions and efforts on product and vendor selection, according to Merrihew. Moreover, they “met individually with physicians in order to understand their needs and thoughts outside of a group environment, worked with Perioperative Services to understand the operational changes that may be impacted by a product change and worked to build a strategic relationship with the vendors,” she noted.

Working together in an academic setting with the orthopedics chair, they achieved a sole-source agreement for hips and knees, and narrowed the number of spine product vendors to two, which alleviates clinical product variation and reduces costs.

The organization’s Medium Impact Supply Chain Committee functions as a value analysis team for items costing $50,000 or less. The MISC includes physicians, other clinicians, clinical engineering, safety and finance professionals. Shane Chapman, M.D., serves as the official Supply Chain Physician liaison, according to Merrihew. Krista Merrihew, R.N., serves as Director, Clinical Quality Value Analysis (CQVA) and Strategic Sourcing. Together, they set CQVA agendas, call meetings and facilitate discussions.

The MISC discusses product requests brought to it in a standard format that includes clinical need, product efficacy, product cost, total cost of ownership, return on investment and reimbursement terms.

“It helps to have a physician assume such a leadership role when making clinical product decisions. It also helps that Dr. Chapman sees patients several times a week. It lends to the credibility of the position and department,” Merrihew added.

Collaborating with clinicians doesn’t have to be complicated, Merrihew insisted.

“Do what you say you will,” she advised. “Learn what they are trying to accomplish, set a strategy together and let them know you are trying to help them. Bring useful accurate data to the discussion, both financial and clinical. It also helps to hold one-on-one meetings with clinical stakeholders prior to any group meetings. This builds trust and collaboration.”

Innovation means business

Fostering innovation within Supply Chain required fomenting a new mindset that eschewed a risk-averse mentality, while building on fundamentals.

“If you place your hand too close to fire and get burned, you are hesitant to go near fire again for fear of getting burned again,” Lancaster noted. “In the supply chain, this mindset causes you to become entrenched in safe activities that have value but don’t have the contemporary or transformational outlook needed to support the clinical enterprise. Old school, transactional thinking with limited vision and no strategic plan are opposite of our mindset of embracing the improbable and challenging existing processes.

“This comfort also happened over time, supported by lack of understanding of the true value the Supply Chain can offer,” he continued. “Decentralized contracting and sourcing and lack of control over all supply chain functions led to lack of control and visibility of possible issues and unrealized value. Over the last few years our team has transformed through system methodologies, documented and supported [standard operating procedures] and trust within the organization at the highest level.”

Lancaster references a basketball analogy to explain their developmental, team-building strategy.

“You teach fundamentals like dribbling and layups before you introduce a no-look pass and three-point shot,” he said. “We set out to do both at the same time. What we lacked before was the ability to pull the team together in an organized fashion and conduct ourselves as the team. This meant realignment of the team; just like in basketball you don’t need ten centers, you need some forwards, guards and a point guard calling the plays and keeping the team focused. Stepping back and refocusing on fundamentals not only strengthened our output to our organization, but it also helped our team become closer, enabling us to see how we all support each other directly or indirectly.”

The team also recognizes its role extends well beyond supplies into other areas. For example, in purchased services, Supply Chain helped various departments save nearly $2 million in travelers’ costs – supplementary staff to augment areas that cannot hire in a timely manner – to human resources initiatives in insurance and benefits with more than $5 million savings realized or in process, according to Greene.

They track much of this through their financial dashboard, which incorporates their PeopleSoft MMIS ERP module, item master and SCWorx for benchmarking, and is shared with finance monthly and with the C-suite.

“We recognized our data is a source of truth throughout the organization and in multiple systems, and this became a priority for us,” Opolski said. “We work with SCWorx to cleanse and help maintain our item master. They also provide us with analytics like benchmarking and contract compliance. This was all enabled by a Data Governance structure and process we established when we embarked on the quest for a single system-wide item master. This governance included the creation of a Data Rulebook where rules for item descriptions and maintenance are memorialized.”

Supply Chain also inserted three staffers in the Operating Room to ensure product availability, address quality concerns and avoid expedited freight charges.

“They are actually Supply Chain Technicians we’ve taught to look out for supply issues, but also serve as customer service agents within Periop acting as navigators with the periop staff,” she added.

To more efficiently manage outdated equipment and capital replacements, Dartmouth-Hitchcock created a reverse logistics process for these “hidden assets.” Through this process they’ve sold used, functioning equipment that generated several hundred thousand dollars, according to Michael Ackerman, Strategic Sourcing Specialist. They work with auction brokers to sell to Third World healthcare facilities and also deal with smaller, budget-driven facilities in closer proximity.

“The project is in its infancy, but we are currently selling our capital and medical assets to five vendors,” Ackerman said. “We haven’t found one vendor that always gives us the best price, so we leverage all offers. We also sell and/or trade to our system members and NEAH.”

To gauge customer satisfaction levels with service provided, Supply Chain rolled out HappyOrNot’s survey tool to gain quick insights from a smiling face to a sad face at the push of a button, according to Casano. Their motivation? Formal meetings are not always conducive to the customer sharing true feelings, he indicated.

“We thought that real-time alerts based on how things are going throughout the day would be a nice way to hear the voice of the customer in a different way, Casano said. “It helped us to identify which units were having some concerns and also which time of the day so we could diagnose the problem. Was it a product availability issue, customer service, communication breakdown?, as examples. This allows us the ability to focus our resources where they are needed and to learn how to better connect.”

The lessons were enlightening.

“We learned that a nursing floor tech took the supplies from the clean supply room and moved them to supply carts at a certain time of day and then the clean supply room was empty of a few products,” Casano recalled. “This was a quick fix. Another time we learned there was a change in practice that caused product to run out and this alerted us to the problem. Anything that helps to increase communication with our customers and allows us close to real-time monitoring of performance means we can increase our ability to serve our customers. The better we support the clinical teams, the better the patient experience is. We are here for our neighbors, our friends and our family – those are our patients.”

Dartmouth-Hitchcock Supply Chain team salutes supplier partners

Alvarez & Marsal is our trusted advisory firm that helped us develop and implement our Strategic Plan, thereby establishing the beacon that guides us.

Greenhealth Exchange serves as a valuable forum for moving to suppliers that provide a “green perspective.” This has helped us incorporate the habit of assessing suppliers from multiple dimensions, not just cost.

Green Mountain Messenger provides us with courier services in New England. Their flexibility and responsiveness has allowed us to respond to emergent needs, but more importantly to expand our logistics network, while helping us focus on a green solution.

Hammond & Ebersole is our workforce development partner that has worked directly with Supply Chain leadership and staff on developing people through regular group meetings, personal coaching, mindfulness and empowerment.

Lumere (which is part of GHX) provides us with a useful workflow solution that has become a valuable tool to standardize and streamline the product request process.

Resilinc plays a key role in supplier resiliency transparency for us, providing real-time and on-demand data on global supply disruptions.

Surgery Exchange provides the technology that links our case volume with vendors and plays a critical role in efficient demand planning.

As our primary distribution partner, Medline has helped enhance logistics efficiency at our central warehouse and supplies cost-competitive, self-manufactured products.

Medtronic became a strategic partner through true transparency, while partnering to enable our demand-planning pilot. We also served as a beta site for their field inventory management solution driving efficiency in surgical scheduling and OR efficiency.

PartsSource represents our partner for cost-competitive equipment and capital planning that has enabled us to build a reliable, three-year capital replacement plan.

Ricoh provides us with the right equipment and print solutions that allows us to develop and implement in-house print services. Our Print services department is market-competitive from both price and product standpoint.

Our data analytics partner SCWorx assisted us in developing a single, system-wide item master. Through their process and dashboard, we perform item master maintenance, contract compliance and benchmarking activities.

Vizient Advisory Solutions has helped us realize significant cost savings and value through contracting, performance improvement and alignment with our goals.

Our office supplies partner WB Mason continuously brings us new products and services, adapts to changing requirements and has helped us save money without sacrificing quality.

While we slowed our work with Zipline due to the pandemic, we felt it necessary to partner with a leader in the drone industry to get a sense of how that technology within the context of healthcare delivery would function. We found them to be a leading-edge solution to help us “Think Different.”

Demand-planning strategies predate pandemic, but produce perseverance

by Rick Dana Barlow

Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health’s award-winning Supply Chain division embraced demand planning strategies well in advance of the coronavirus pandemic that exploded four months ago.

Fortuitous foresight? Perhaps. Yet their early efforts were not rooted in stocking ample personal protective equipment (PPE) and disinfection products, but in orthopedic implants.

“Medtronic approached us about helping them reduce the amount of inventory they had in sales reps trunks,” explained Richard Casano, Director, Supply Chain Operations. “The sales rep is not a supply chain-trained professional and is incentivized to always have the products needed to support a case. This caused them to have duplicative products deployed in the same region because sales rep A doesn’t want to let sales rep B have a product [as] they might need that product themselves the next day. This was for the spine group. They had seen that we were providing them visibility to orders electronically through our partnership with Surgery Exchange. We put together a pilot whereby our case data was transferred to a new tool they were developing to provide improved inventory management in the field. This allows us to do advance case panning and order products that are needed in advance and not sit on a large quantity of inventory.

“This solution allowed our team and theirs to see exactly what the surgeon would be using for each case on a specific day resulting in a reduction of consignment inventory, decreased risk of loss or damage of consignment product and reduction of Medtronic’s assets in the field, thus helping us to leverage this knowledge and lower both organizations’ cost to serve,” he added.

Supply Chain chose to start the project small with a pilot for a specific product line, according to Casano. They isolated useful data for the vendor, which included case volume notated weeks in advance, but recalibrated as cases were changed, scheduled or canceled. Until the demand planning project began, case scheduling didn’t incorporate the needed product specificity. The physician and sales rep would connect directly with a 24-hour window to supply product.

“Our approach was less elegant in terms of demand and supply mapping in that we meshed together various data sources and devised estimates for utilization by type of procedure,” Casano indicated. “We also built in a robust fudge factor so that we wouldn’t be caught short. In the end, the models worked for us. As we become more sophisticated, I’d like for us to incorporate AI and predictive and prescriptive analytics into our models.”

Shining the VAT signal

Transmitting an electronic demand signal to the manufacturer directly helps manage a more efficient supply chain through the effective use of information.

“The device maker benefits from information that allows them to manufacture a more accurate supply to meet demand,” he stated. “We benefit by sharing in the economic gains of reducing vendor inventory costs, less clutter, and greater visibility as to what and when products will be in our OR. Before this, we had consigned product on hand just in case we needed it. This meant we had large quantities of high-dollar supplies in our walls that were manufactured in case we needed it and placed at our facility.”

Then the coronavirus erupted into a pandemic.

“The pandemic blows traditional demand planning out of the water,” Casano admitted. “[COVID-19] validated our overall strategy but amplified the need to change how we need to meet the market. In the end, people proved critical to our successful response to COVID. Our staff was creative in sourcing, a trait we now foster. So it’s not so much that COVID affected our original plan as much as our original plan enabled us to respond, pivot and think different.”

One component of their pre-pandemic demand-planning strategy involved partnering with a company called Resilinc that enabled the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Supply Chain division to know about real-world disruptions that may affect the manufacturers they use as well as their finished products, components, packaging and raw materials.

“This doesn’t just say this is a backorder or recall, but it literally alerts us to issues across the supply chain like rioting, weather events, or as the alert informed us on January 4 of a mystery virus infecting dozens in China,” Casano said. “This put the COVID-19 coronavirus on our radar early.”

The team saw obvious value in gaining a head start.

“We could see the value of the event watch alerts based on getting burned once by the hurricane that wreaked havoc in Puerto Rico and knowing other events would occur equally devastating to a supply chain,” he said.

Supply Chain actively maintains a hotspot tracking monitor in its office foyer at all times, according to Casano. Resilinc highlights hotspots on the displayed world map, lists current events that may affect supply chain routes and tracks manufacturer production facility resiliency in the context of any proximate events. Production can be interrupted by earthquakes, fires, power outages, rain, wind or even labor union strikes.

“We submit our high-volume manufacturers to Resilinc who engage the manufacturers in order to probe into their supply sources,” Casano said. “We also ask for information on their recovery times in the event of a disruption, a ramp-up period if they need to go to a new manufacturing location, and subcontractors they use in the manufacture of their product. We will be using this information to tighten some relationships, but also to change how we negotiate contracts based on the risk we are accepting from doing business with the manufacturers.”

Global watchtower

As the coronavirus outbreak exploded from epidemic to pandemic, the Supply Chain team could spot countries were enacting stay-at-home orders and how those decisions could impact areas outside China, according to Casano. “If computer chips used in radiology machines aren’t available because workers aren’t going to work, should we forward buy to make sure we have a quantity on hand?” he added.

Dartmouth-Hitchcock’s Supply Chain demand-planning process is monitored by a dedicated team that receives e-mail, text and live-streamed updates on a dashboard, according to Casano. The team includes the Demand Planning Manager Anna Pinilla, Manager of System Procurement Nick Metcalf, System Inventory Controller Steve LaTorre, Director of Supply Chain Operations (Casano) and an external supply chain consultant, Zach Wilson. This group estimates the overall length of the disruption. “We then move to capture what we can from the primary source and now have ample time to find secondary or tertiary sources,” he added.

“In the case of COVID-19, we used a combination of technology and experience to identify there was a problem,” Casano recalled. “Back on January 4, we received the alert about the emerging virus and knew something was happening in Wuhan, where many of our products are manufactured. Our VP [Curtis Lancaster] was talking to his counterpart at the UVM Health Network [Charlie Miceli, Vice President and Network Chief Supply Chain Officer] and realized that with all the people going to China for the Chinese New Year there was a chance of greater spread. We then began ordering PPE by the boatload (literally), air, and leveraging our distribution channels for all PPE. It gave us a head start.”

Supply Chain’s technology-infused premonition drew sighs of relief from their customers.

“Once we recognized that PPE would be an issue, we instituted a daily supply-and-demand report that communicated specific PPE supplies on hand and on order,” noted Leah Greene, Business, Manager, Supply Chain. “This instilled the confidence that we’d have enough supply to satisfy demand. Regarding some of the more sophisticated aspects of demand planning, we plan to incorporate more market intelligence into our models leveraging solutions like Resilinc, and eventually add AI to the mix for predictive modelling given a certain set of known and unknown variables.”

Within a month of recognizing the pandemic, Dartmouth-Hitchcock’s glove supply ballooned to 665,000 products on hand from 3,700 pairs pre-coronavirus, and its N95 respirator volume mushroomed to more than 500,000 on hand or on the way from 3,100, calculated Krista Merrihew, Director, CQVA and Strategic Sourcing.

“We had some orders placed early but continued to source from multiple avenues to ensure a continuity of supply,” Merrihew indicated. “We had been actively using the [Resilinc] software for almost a year to identify areas across the globe that were experiencing natural or political crisis to help us to stay ahead of supply shortages.”

Naturally, Supply Chain needed space to store all of this additional product.

“The first week of April, we developed a supply distribution depot in one of our large auditoriums and leased local warehouse space, providing just-in-time distribution of PPE supplies, respirator and PPE cart rounding,” Merrihew noted. “This helped to prevent hoarding of supplies and helped us to track demand by unit. Our team was also there to answer questions and direct departments to resources for what to use, how to use it and when.”

The auditorium was located in the flagship Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center and the off-site warehouse included 30,000 square feet of storage space for PPE and other critical supplies. Respirator rounding and PPE cart monitoring occurred 24/7, she added.

No matter how well-planned, the process did engender some “intentional and strategic scrambling” linked to changing requests and supplier effectiveness, according to Joseph Opolski, Director of Capital, Contracts, and Alliances.

“As an example, when the organization realized we needed to staff all entrances and needed infrared thermometers, there was a scramble to source them since this is not an item that we would need in such large quantities historically,” Opolski said. “The impact of the coronavirus on Chinese manufacturing in Wuhan and the risk of spread beyond China were early signals that the demand for PPE would very likely increase while supply would be constrained. We feared that our normal suppliers would soon struggle to meet our PPE needs so we increased our order quantities, ordered products from secondary suppliers and purchased alternative products. As the virus started to spread beyond China, we began sourcing ‘gray market’ suppliers and local manufacturers.”

They also faced opportunists and profiteers but collaborated with The University of Vermont Health Network (UVM) to ward off risks and reap rewards.

“During this period, we worked closely with [UVM] to chase down leads and vet unfamiliar products, manufacturers and suppliers,” he noted. “Working collaboratively with another health system allowed us to apply more resources and aggregate volume to participate in bulk buys and make our purchase order quantities more attractive to suppliers.”

Adding new perpetual inventory with interim storage space in the auditorium and new warehouse space while incorporating stock into the PeopleSoft ERP system represented challenges.

Early on Dartmouth-Hitchcock was able to access some temporary space through UVM and Dartmouth College.

“The new spaces allowed for receipt and storage of products, but monitoring inventory levels and moving products across our system from three separate facilities created logistical challenges for an operations team that was already stretched with supporting the hospitals pandemic response,” Opolski said. “Accounting for new products, existing products with new prices and creating new inventories also put a strain on IT, Finance, and our Technology team overseen by Supply Chain Technology manager Robin Boylston as they endeavored to keep up with changing operational requirements.”

Within a month or two they were able to consolidate the additional stock to the leased warehouse space from the three other sites.

Curtis Lancaster, Dartmouth-Hitchcock’s Vice President, Supply Chain Division, credits their GPO Vizient for pulling together a “war room” and providing advocacy and support, and salutes UVM Health Network’s cooperation “to divide and conquer” the tasks before them, including vetting products and vendors, communicating daily at first before settling in at weekly intervals.

Beacon of hope

The role of demand planner and position of demand planning manager may be common outside of healthcare, but it’s certainly rare and unique to healthcare. The person sought and hired for the role must be cognizant of the herculean tasks and responsibilities that await him or her.

“You need someone that is multifaceted, has been in different roles and understands the desired goal and outcomes,” Casano described. “You need someone that is driven because this is a HARD thing to introduce into the healthcare industry. You need to have someone that is motivated and can execute. You need someone that can work with all internal and external members, appropriately keeping them focused and motivated. This individual needs to understand what motivates not only the organization but each stakeholder and influence them into the change in practice, thoughts and ideas. You need someone that can reprioritize and drive results. You need someone who is curious, has grit, and is relentless. You need someone that can get stuff done.”

Based on their experience with spinal products and pandemic response, the Supply Chain division naturally expects to expand demand planning to other service lines.

Lancaster stresses the importance of open and fluid communication so that everyone is on the same page.

“We are not perfect, but we do our best to keep all Supply Chain leaders informed of what we are doing,” he said. “We do this through a pipeline of opportunities with a dashboard of progress. The Supply chain Leaders from across the system have a touch-base huddle every M-W-F at 7:30 a.m. to answer questions and follow up. The Supply Chain system leadership has a weekly meeting, and we include our consulting partners to join this. We have multiple check-ins. Overlaps remain, but we work quickly through updates to discover them and get aligned. Our team, our stakeholders, our trading partners know our plan. We know our roles. This minimized overlap, duplication, redundancies and inefficiencies as best we can. The strategic plan gave us the beacon. Now we’re all moving toward it.”

Dartmouth-Hitchcock’s Supply Chain team shares mindsets, milestones that motivate success within their enterprise

Lebanon, NH-based Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health’s Curtis Lancaster, Vice President, Supply Chain Division, shared with Healthcare Purchasing News Senior Editor Rick Dana Barlow his team’s attitudes and motivations behind what, how and why they do what they do with valuable insights on what helps them succeed.

HPN: What’s the secret formula that makes a leader in supply chain management? How does your division implement that secret formula?

LANCASTER: It’s people. People are our foundation. We invest in people. We make them an integral part of our strategy. The secret formula is to highlight and rely on the strengths of our individual team members. We have unique talent in our department and it is incumbent upon our leaders to identify these strengths in others to help them flourish. We have a number of people on our team who have worked their way through the organization and are now in roles where they are thriving. We’ve always believed that “a rising tide lifts all boats.”

The next big trend in healthcare supply chain management will be...[fill in the blank]. Why?

I’m hesitant to isolate one trend as this year has shown we need to be responsive to market dynamics on several fronts at the same time. But one significant trend will be “the last mile” – getting supplies and services to patient’s homes as more care is delivered outside the acute care setting. This will be enabled by telehealth, drones, distributed logistics (vs. centralized). This is especially true for Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health (D-HH) as many of its patients are in rural, remote areas. Another trend will be the movement towards making the supply chain more resilient. This will likely take several forms, including moving more production to North America, as well as new roles created for Demand Planning and forecasting analytics. I think that the consumer, the healthcare providers in this case, will get closer to the manufacturing sources that remain offshore. This will reduce the risk that a third party can impose such as dictating reduced allocation or driving mark-ups.

Some in the “C-suite” have criticized supply chain managers for being too technical and not strategic enough to “join their club.” Do you agree? Why?

That’s the challenge the industry has endured for decades now. Many don’t see the Supply Chain as a strategic enabler, one that can help the organization achieve its overall goals. Instead, it comes down to getting the lowest price for something. We changed this by developing our own strategic plan that aligns with the goals of the organization.

How can consulting firms, distributors and GPOs contribute to the performance of your internal supply chain management expertise without overshadowing the department/division or usurping control?

Clear expectations for all involved and the understanding that organizational value is what we all strive to achieve without worrying who gets specific credit for the work. All these trading partners are critical enablers of our Supply Chain Strategy. They don’t overshadow us because they have been integrated into our Supply Chain Strategy as active participants. They know where they fit in the plan, their role, and oriented toward the beacon of where we are headed.

What specific project did your division complete where you felt they exceeded your expectations?

Executing on our strategy. The team helped advise us on the strategic plan but then have spent the last 18 months executing against that plan.

In your opinion, what is your division’s toughest administrative challenge? How might you solve it?

By administrative, I’ll address that from a system organizational standpoint. Our biggest challenge is when we are not involved in the sourcing process from the start and throughout the organization. We continue to spread our influence beyond supplies to purchased services. This has proved to be a challenge in the past in that our proactive efforts to get involved early were seen as meddling. We have solved this in several ways. One: Lead an overall Margin Enhancement initiative that encompasses leadership and stakeholders across the system. Our role is seen as an enabler in terms of sourcing potential suppliers, evaluating them, and moving them through the contracting process. Two: Educate stakeholders that their budget goals cannot be achieved solely by Supply Chain. We must do this collaboratively with the budget owners; they’ve come to realize that they ultimately control the dollars, we don’t.

What is your division’s toughest operational challenge? How might you solve it?

Operationally, I think it’s been the exchange of information between our vendors and us. Specifically, the information that would give them and us the ability to respond to our demand and their supply. We are solving this with our demand-planning function. To start, we piloted a solution between us, Medtronic and Surgery Exchange to facilitate the exchange of case information between these trading partners. While we are assessing the pilot, we plan to expand to other vendors and service lines.

What are your top three priorities for the remainder of 2020 and for 2021?

Recover from the financial and operational consequences of the COVID pandemic. We are evaluating unique and novel ways to bring our community back together and recover financially from the past three months.

Utilize demand planning and resiliency to better position our Supply Chain for future challenges like pandemics, financial pressures, or changing delivery models.

Refresh our strategy to get closer to our manufacturers, expand our reach as a fully-integrated Supply Chain at D-HH as we continue the work of enhancing the value locally and regionally through the New England Alliance for Health (NEAH), and continue to expand on our work as a clinically-integrated supply chain with Clinical Quality Value Analysis and clinical relationships.

How does the CEO view your division? Does she see it as a strategic function or a support service? What resources can the division count on and will they come every year – and not just in response to clinician complaints?

We received a lot of kudos due to our response to the pandemic. We anticipated, planned and executed creatively and early. This was called out several times by the CEO. In fact, she asked us to develop a presentation on how we responded, including stories from the trenches, lessons and lots of pictures (mostly of PPE). Our success reinforced that we are a critical enabler of the overall system strategy. It doesn’t hurt that we aligned our Supply Chain Strategic Plan with System objectives, i.e., supporting growth outside of the acute care setting. It’s this alignment that got us to the leadership table and it’s this alignment that has allowed us to do creative things.

What are some practical, common sense ways that supply chain managers can keep patient satisfaction in mind as they’re performing their duties?

Walk around regularly and be visible. Don’t stay in your office, the basement or the dock. See the work you do and how it supports patients getting the care that they need. Talk to your internal customers daily. You have to see that you, in fact, “Support the Hands That Heal.”

If you could change one C-suite and clinical (physician/nursing) perception of your division, what would it be and why?

Getting those stakeholders who consume supplies and services to understand that they are the most important influencer in terms of product and service change. Resource control, margin enhancement begins and ends with them. The Supply Chain enables them. We have solved this through education, specifically outlining the role of the Supply Chain in our marketing document.

How can supply chain managers collaborate with other departments and professionals and convince them that their decisions are based on the financial health of the organization and not in denying them quality products or dictating patient care as the clinicians might tell the CEOs?

Lead at the table with humble knowledge and total value. You may not have the right answer all the time, but you can bring accurate financial and clinical information to help support decision making. Understand a holistic point of view to balance financial and clinical decision making and reach the intersection between the two.

What advice do you have for professionals outside of healthcare wanting to enter into the field of healthcare supply chain management (whether college students or from other industries)?

This is a great industry to make a career with many opportunities for advancement and interesting work. There is tremendous opportunity to make real positive contributions that impact people’s health and lives. Getting the right supplies at the right time is critical to patient care. You can make a difference. And with an organization that puts people as a central pillar of its strategy, the opportunities are tremendous.

About the Author

Rick Dana Barlow

Senior Editor

Rick Dana Barlow is Senior Editor for Healthcare Purchasing News, an Endeavor Business Media publication. He can be reached at [email protected].